In a world often dominated by aggressive competition and conflict, Aikido stands as a unique martial art that emphasizes harmony and non-violence. Developed in Japan by Morihei Ueshiba in the early 20th century, Aikido is more than just a method of self-defense—it is a philosophy, a way of life. Unlike many martial arts that focus on overpowering an opponent, Aikido teaches practitioners to blend with an attacker’s energy, redirecting it in a way that neutralizes the threat without causing unnecessary harm. This principle of harmony, known as "ai-ki," is at the heart of the art and reflects its deeper spiritual roots.

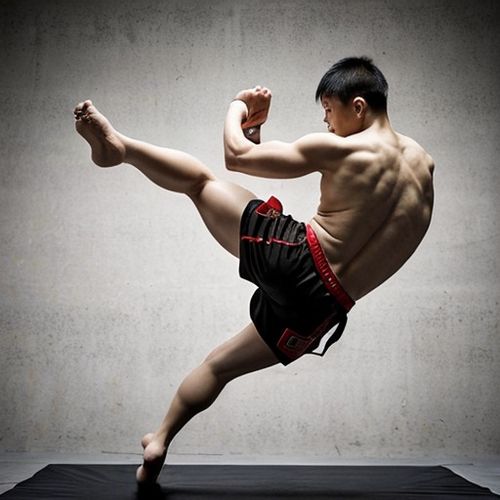

The techniques of Aikido are fluid and circular, designed to use an opponent’s momentum against them. Throws, joint locks, and pins are executed with precision, but the goal is never to inflict injury. Instead, the aim is to control the situation and restore balance. This approach makes Aikido particularly appealing to those who seek a martial art that aligns with ethical and philosophical values. Many practitioners find that the lessons learned on the mat—patience, mindfulness, and respect—extend into their daily lives, fostering personal growth and a deeper understanding of human interaction.

The Philosophy Behind the Art

Morihei Ueshiba, often referred to as O-Sensei (Great Teacher), envisioned Aikido as a means to unify the body, mind, and spirit. He believed that true martial arts were not about defeating others but about overcoming the conflicts within oneself. Ueshiba’s spiritual journey, influenced by Shintoism and Omoto-kyo (a Japanese new religion), deeply shaped Aikido’s principles. The art’s techniques are not merely physical maneuvers but expressions of a broader philosophy centered on peace and reconciliation. This is why Aikido is sometimes called "the art of peace."

One of the most striking aspects of Aikido is its emphasis on non-resistance. Rather than meeting force with force, practitioners learn to move with an attack, blending their energy with that of the aggressor. This concept can be challenging to master, as it requires letting go of the instinct to fight back. However, once understood, it becomes a powerful metaphor for resolving conflicts in life. The idea is not to avoid confrontation but to transform it into something constructive. In this way, Aikido transcends the boundaries of a traditional martial art and becomes a tool for personal and societal harmony.

The Physical Practice of Aikido

Aikido training typically begins with learning how to fall safely, a skill known as ukemi. This is essential because much of Aikido involves being thrown or rolling out of techniques. Ukemi is not just about physical safety; it also teaches humility and trust, as practitioners must learn to surrender to the momentum of a technique. From there, students progress to basic movements (taisabaki) and techniques such as irimi (entering) and tenkan (pivoting). These foundational skills are repeated endlessly, as precision and timing are critical in Aikido.

Unlike competitive martial arts, Aikido does not involve sparring or tournaments. Instead, practice is conducted in a cooperative manner, with partners taking turns attacking and defending. This cooperative training fosters a sense of mutual respect and shared learning. Advanced practitioners often explore weapons training, including the wooden staff (jo), wooden sword (bokken), and knife (tanto), which further refine their understanding of movement and distance. However, even weapons techniques in Aikido are rooted in the same principles of blending and redirecting energy.

Aikido’s Global Influence

From its origins in Japan, Aikido has spread across the globe, attracting students from all walks of life. Its appeal lies in its universal message of peace and its adaptability to different cultures and contexts. Dojos (training halls) can now be found in nearly every country, each adding its own cultural flavor to the practice. Some schools emphasize the spiritual aspects of Aikido, while others focus more on practical self-defense applications. Despite these variations, the core principles remain unchanged.

In recent years, Aikido has also found applications beyond the dojo. Its principles have been incorporated into conflict resolution programs, leadership training, and even therapy. The idea of blending with energy and finding peaceful solutions resonates in fields as diverse as business management and psychology. This versatility is a testament to the depth of Aikido’s philosophy and its relevance in the modern world.

The Challenges and Rewards of Aikido

Learning Aikido is not easy. It requires patience, dedication, and a willingness to let go of ego. Progress can feel slow, as the art’s subtle techniques often take years to master. Unlike more aggressive martial arts, Aikido does not offer the immediate gratification of overpowering an opponent. Instead, it demands introspection and a commitment to personal growth. For many, this is precisely what makes it so rewarding.

Long-term practitioners often speak of Aikido as a lifelong journey. The physical techniques are just the beginning; the deeper lessons—about harmony, resilience, and compassion—unfold over time. Whether practiced for self-defense, fitness, or spiritual development, Aikido offers a path to greater self-awareness and a more peaceful way of engaging with the world. In an era of division and conflict, its message is more relevant than ever.

By James Moore/May 8, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/May 8, 2025

By Emily Johnson/May 8, 2025

By James Moore/May 8, 2025

By Joshua Howard/May 8, 2025

By Noah Bell/May 8, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/May 8, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/May 8, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/May 8, 2025

By Noah Bell/May 8, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/May 8, 2025

By Christopher Harris/May 8, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/May 8, 2025

By Sarah Davis/May 8, 2025

By Joshua Howard/May 8, 2025

By Sarah Davis/May 8, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/May 8, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/May 8, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/May 8, 2025

By Noah Bell/May 8, 2025