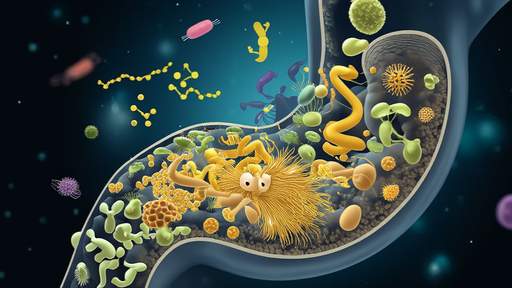

The human gut microbiome – often called our "second brain" – thrives on what we feed it. This complex ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms influences everything from digestion to mood, immunity, and even cognitive function. Just as we carefully select fuel for our bodies, we must thoughtfully nourish these microscopic allies through strategic dietary choices.

At its core, a microbiome-friendly diet resembles the eating patterns of our ancestors – abundant in fiber, fermented foods, and polyphenol-rich plants. The modern Western diet, high in processed foods and low in variety, has been shown to reduce microbial diversity by up to 30% compared to traditional diets. This depletion may contribute to the rising incidence of inflammatory diseases, obesity, and mental health disorders observed in industrialized nations.

Fiber forms the foundation of microbial nourishment. Unlike other nutrients that get absorbed in the small intestine, dietary fiber reaches the colon relatively intact, where it becomes fodder for beneficial bacteria. These microbes ferment fiber into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) – particularly butyrate, acetate, and propionate – which serve as both energy sources for gut cells and signaling molecules for systemic health. The average Westerner consumes only 15 grams of fiber daily, while our hunter-gatherer ancestors likely ate 100-150 grams. Aiming for at least 30-50 grams from diverse plant sources can significantly improve microbial diversity.

Not all fibers are created equal. Resistant starch, found in cooked-and-cooled potatoes, green bananas, and legumes, preferentially feeds Bifidobacteria. Inulin-type fructans from chicory root, Jerusalem artichokes, and garlic boost beneficial Lactobacilli. Beta-glucans in oats and mushrooms support overall microbial balance. The key lies in variety – consuming at least 30 different plant foods weekly provides the diverse polysaccharides that different microbial species require.

Polyphenols, the colorful compounds in plant foods, serve as both microbial food and medicine. These bioactive molecules often reach the colon largely unchanged, where gut bacteria transform them into more absorbable forms with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Berries, with their anthocyanins, enhance Akkermansia muciniphila – a bacterium associated with lean body mass and metabolic health. Flavanols from cocoa and tea promote butyrate-producing species. Even coffee polyphenols selectively feed certain beneficial strains while inhibiting pathogens.

Fermented foods represent the most direct way to introduce beneficial microbes. Traditional preparations like kimchi, sauerkraut, kefir, and kombucha contain live cultures that can transiently colonize the gut. Regular consumption has been shown to increase microbial diversity and reduce markers of inflammation. Interestingly, the benefits extend beyond the probiotics they contain – the fermentation process itself breaks down anti-nutrients and creates new bioactive compounds that support gut health.

Prebiotic foods deserve special attention for their ability to selectively nourish beneficial bacteria. Garlic, onions, and leeks are rich in fructooligosaccharides (FOS) that stimulate Bifidobacteria growth. Asparagus and jicama contain inulin that feeds Lactobacilli. Even unexpected foods like seaweed provide unique polysaccharides that support specialized marine bacteria that may have colonized human guts through coastal diets.

The timing and combination of foods matters as much as the foods themselves. Consuming polyphenol-rich foods with prebiotics enhances their bioavailability – think berries with oats, or dark chocolate with almonds. Eating fermented foods with fiber gives the probiotics the fuel they need to establish themselves. Even simple practices like chewing thoroughly can improve microbial access to nutrients by breaking down plant cell walls.

Emerging research suggests our microbes follow circadian rhythms, making meal timing potentially important. Some studies indicate that time-restricted eating aligned with daylight hours may benefit microbial diversity. The microbial fermentation process produces gases and other byproducts that are easier to process during waking hours. Nighttime eating, especially of hard-to-digest foods, may disrupt both human and microbial circadian cycles.

Hydration plays an underappreciated role in microbial health. Water supports the mucosal lining where many bacteria reside, and mineral waters containing magnesium or sulfate can have prebiotic effects. Herbal teas provide both hydration and polyphenols, while excessive alcohol can damage the gut lining and alter microbial composition.

Personalization is key when feeding your microbiome. While general principles apply to most people, individual responses vary based on baseline microbiota, genetics, and lifestyle. Some may thrive on abundant legumes, while others need to introduce them gradually. Paying attention to digestive comfort and energy levels after meals can guide personalized adjustments. Advanced testing now allows for microbiome analysis, though dietary experimentation often proves equally informative.

Beyond specific foods, overall dietary patterns create the environment where gut microbes either flourish or struggle. The Mediterranean diet, rich in plants, olive oil, and fish, consistently shows positive effects on microbial diversity. Traditional Japanese and Nordic diets similarly support gut health through fermented foods, seafood, and seasonal plants. Even within these patterns, incorporating a wide variety of ingredients prevents microbial "monocropping" and promotes resilience.

Processed foods often contain emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, and preservatives that may harm beneficial bacteria while promoting less desirable species. Not all processing is equal – canned beans or frozen berries retain most of their microbiome benefits – but highly refined products with long ingredient lists typically offer little microbial nourishment and may actively disrupt gut ecology.

Stress management and adequate sleep profoundly influence gut health through the gut-brain axis. Chronic stress can alter gut permeability and microbial composition, while quality sleep supports microbial diversity. These lifestyle factors work synergistically with diet – no amount of kimchi can fully compensate for chronic sleep deprivation or unmanaged stress.

For those transitioning to a microbiome-friendly diet, changes should be gradual to allow both the gut and its inhabitants to adapt. Suddenly increasing fiber intake can cause discomfort if microbes aren't prepared to handle it. A slow, steady approach – adding one new plant food or fermented item each week – tends to yield better long-term compliance and microbial shifts.

The gut microbiome's responsiveness to dietary change offers hope – significant shifts can occur within days to weeks of altered eating patterns. While some microbial signatures appear stable long-term, the functional capacity of the microbiome changes rapidly with diet. This plasticity means it's never too late to start feeding your microbial partners more thoughtfully.

Ultimately, nourishing our gut microbes represents a profound act of symbiosis. The foods we choose determine which species thrive, and in turn, those microbes influence our cravings, metabolism, and even mood. By mindfully selecting foods that feed our microbial allies, we cultivate an inner ecosystem that supports every aspect of our health – from immunity to mental clarity. This ancient partnership, refined over millennia of coevolution, continues to shape our wellbeing one meal at a time.

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025

By /Jun 5, 2025